Our Expanding Universe

Charting Cosmic Scale and Future Frontiers

Imagine standing on a distant hill, watching dots on a balloon inflate as you blow air into it. Those dots drift farther apart. Now picture our universe doing the same thing, but on a scale that boggles the mind—galaxies racing away from each other, not because they move through space, but because space itself stretches. This cosmic expansion has unfolded for nearly 14 billion years, turning a tiny hot point into the vast web we see today. Back in the 1920s, scientists thought the universe stayed put, like a fixed painting. Then Edwin Hubble changed that view with his telescope work. He spotted galaxies fleeing outward, faster the farther they sat. Our expanding universe isn't just big; it's growing, and that shift in thinking opens doors to wild questions about where it all heads next.

The Discovery of Cosmic Expansion

The Hubble-Lemaître Law and Redshift Explained

Light from far-off galaxies looks stretched when it reaches us. This redshift acts like the Doppler effect you hear with a siren speeding away—waves elongate, shifting colour to red. Edwin Hubble linked this to distance in 1929. He found that the farther a galaxy lies, the quicker it recedes. This Hubble-Lemaître law forms the backbone of our grasp on cosmic expansion. Scientists measure recessional speed using redshift, then tie it to distance with tools like Cepheid stars. The Hubble constant, around 70 kilometres per second per megaparsec, helps us clock the universe's age at about 13.8 billion years. Without this law, we'd miss how the expanding universe evolves.

The Big Bang Model: Our Starting Point

The Big Bang kicked off everything 13.8 billion years ago. It wasn't a blast in empty space. Space itself burst into being, carrying matter along as it grew. Think of raisins in rising bread dough—they spread as the dough expands. This model fits the data we collect. The Cosmic Microwave Background gives proof, a faint glow left from the early heat. Satellites like Planck mapped it, showing tiny ripples that seeded galaxies. Expansion started hot and dense, then cooled as space stretched. We see this in the way elements formed right after the bang. The model predicts our universe's flat shape, matching observations today.

Driving Forces Behind Accelerated Expansion

Dark Energy: The Mystery Dominating the Cosmos

Gravity should pull things together and slow expansion. But it speeds up instead. Dark energy drives this push, making up 68% of the universe's energy. It acts like a spring, forcing space apart on huge scales. We can't see it, but its effects show in galaxy clusters. The leading idea is Einstein's cosmological constant, a steady value in his equations. This constant keeps dark energy levels fixed as space grows. Other theories suggest it changes, but data points to stability. Dark energy reshapes how we view the expanding universe's future. Without it, stars and galaxies might clump more.

Evidence for Acceleration: The Supernova Confirmation

In the 1990s, teams watched Type Ia supernovae, exploding stars with set brightness. These act as standard candles, letting us gauge distances by how dim they appear. Saul Perlmutter, Brian Schmidt, and Adam Riess led the charge. They found distant blasts fainter than expected, meaning galaxies flee faster now. This twist came as a shock—expansion accelerates. Their work earned a Nobel Prize in 2011. "The universe is not only expanding, but expanding faster," Perlmutter noted. Follow-up checks with other tools confirmed it. These supernovae lit the way to dark energy's role in cosmic expansion.

Mapping the Scale: Size, Age, and Observable Limits

Defining the Observable Universe

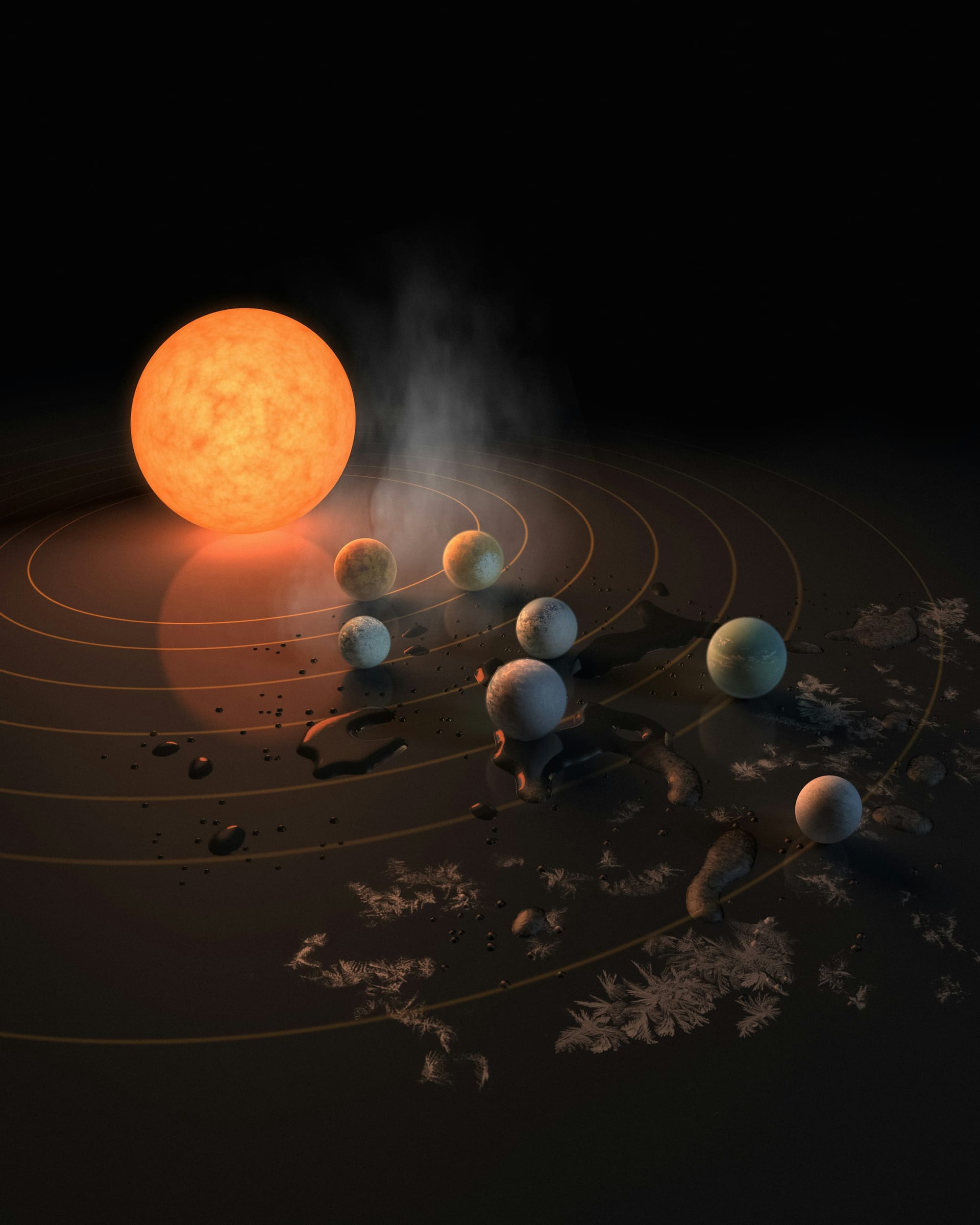

The whole universe might stretch forever. But we only see the observable part, capped by light's travel time since the Big Bang. At 13.8 billion years old, you'd think it's 27.6 billion light-years across. Expansion stretches that to 93 billion light-years in diameter. Light from beyond fades out—we can't spot it yet. This bubble holds about two trillion galaxies. Our Milky Way sits in it, a speck among voids and clusters. The observable universe sets our map's edge for studying cosmic expansion. Beyond? Pure guesswork, but models suggest more of the same.

- Key limits: Speed of light blocks farther views.

- Age factor: 13.8 billion years shapes what we detect.

- Expansion effect: Makes the horizon bigger than raw time suggests.

The Role of Dark Matter in Cosmic Structure

Dark matter differs from dark energy. It pulls, not pushes, making up 27% of the cosmos. We sense it through gravity's tug on visible stuff. Galaxies form in dark matter halos, like glue holding stars. Without it, expansion would scatter everything. Simulations show how these halos clump early on, then spread as space grows. The Bullet Cluster proves it—hot gas collides, but gravity bends light elsewhere, tracing dark matter. It scaffolds the web of cosmic structure amid expansion. Dark energy stretches this web, while dark matter knits the threads.

The Future Trajectories of an Expanding Universe

Fate Scenarios: Big Freeze vs. Big Rip

Dark energy's behaviour sets the endgame. In the Big Freeze, expansion keeps going, thinning energy out. Galaxies drift apart, stars burn low, and heat spreads even. Trillions of years on, black holes evaporate, leaving cold dark. This heat death fits if dark energy stays constant. The Big Rip flips it—if dark energy grows stronger, it tears atoms apart. Galaxies rip first, then stars, planets, and finally quarks. Some models peg this in 22 billion years, but data leans against it. Both show cosmic expansion's power. We watch for clues in future surveys.

Implications for Intergalactic Travel and Observation

Accelerating expansion dooms distant travel. Galaxies beyond the Milky Way's group will vanish from sight. Light stretches too much, redshift hiding them forever. In 100 billion years, our local bubble looks empty. Telescopes like James Webb grab data now. Focus on mapping before it's gone. You can join by stargazing or citizen science apps. This push changes how we plan observations. Intergalactic hops? Forget it—space outruns any ship.

- Watch now: Distant quasars fade soon.

- Local view: Andromeda merges with us, but others flee.

- Tech tip: Use apps to track galaxy speeds yourself.

Living in a Dynamic Cosmos

Our universe expands without end, driven by dark energy after the Big Bang's spark. Hubble's redshift spots the motion, supernovae prove the speedup, and dark matter builds the frame. At 93 billion light-years wide, the observable slice hints at more. We face a Big Freeze likely, with galaxies lost to the horizon. Yet this growth sparks wonder—space, time, and energy weave a tale we chase. Scientists probe deeper with new scopes and math. Dive in: grab a book on cosmology or scan the night sky. What secrets will you uncover in this ever-stretching realm? Share your thoughts below—let's explore together.